All Eyez on Rap & Hip-Hop: Analyzing How Black Expression is Criminalized

By Maia A. Young | Symposium Editor

December 13, 2023

—

. . . and all top of that

They tryin to blame this rap shit for all of our ills

Like I can stick you up with a mic

Like I can rape you with a verse or use a verb as a knife

Like before Kool Herc, everything was alright

Like y’all wasn’t calling Black women hoes befo’ “Rapper’s Delight”[1]

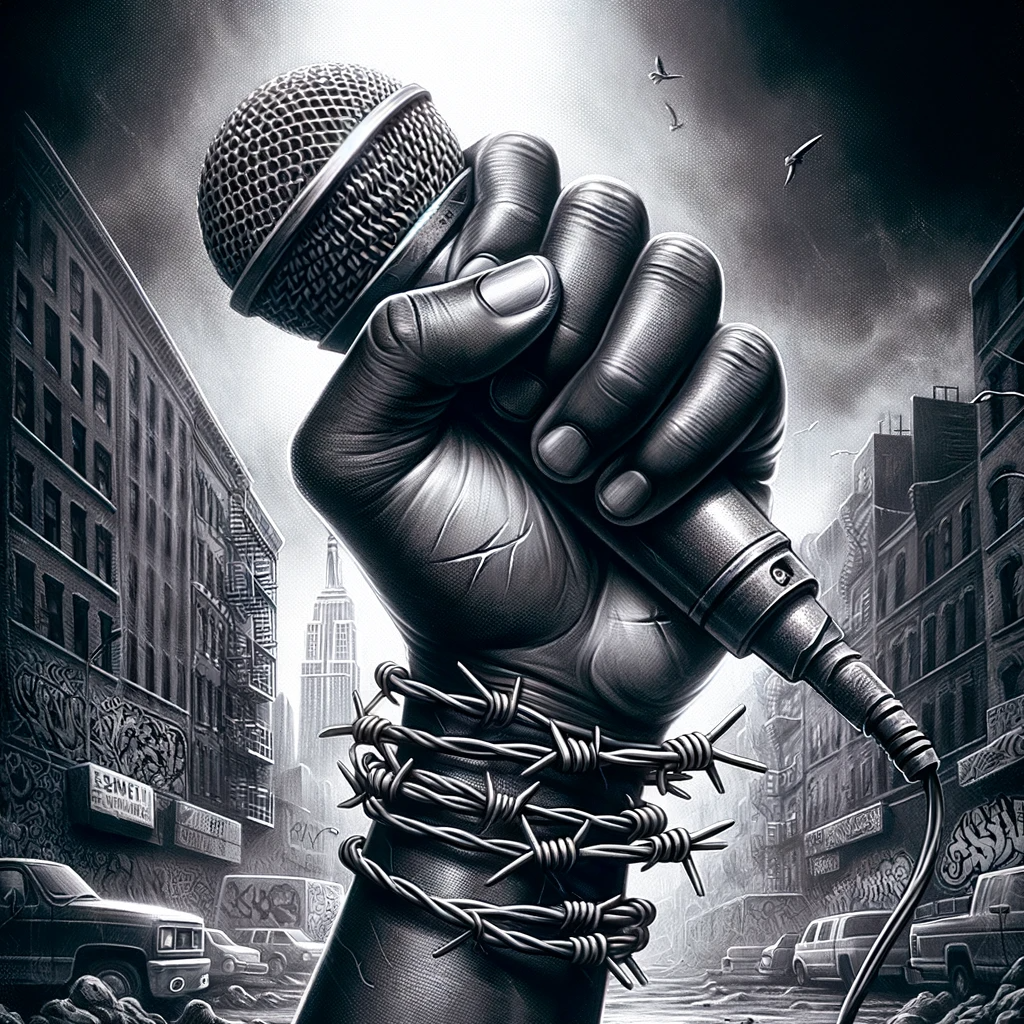

In the trend of allowing rap and hip-hop lyrics to be used as evidence in criminal proceedings, Black expression is now subject to unfair participation in a system that has historically ignored its people and its protest.[2] Perceiving violence or criminal conduct to be exclusively linked to the genres of rap and hip-hop[3] perpetuates America’s thematic history of injustice and misinterpretation of Black life, music, and culture. Accusing rap of causing violence “attempt[s] to erase from the consciousness of [Americans] the history of oppression that [gave] birth to hip-hop culture.”[4] America’s negative perception, yet mass commodification, of rap and hip-hop music is indicative of America’s commitment to engage with Blackness at its convenience.

Rap music is a powerful force for identity and solidarity.[5] Rap, in essence, is a transformative art form that provides a social commentary, narrowed in the lens of cultural understanding.[6] Through its lyricism, rap music confronts hyper policing in Black communities, mass incarceration, and other problems faced by Black and brown communities head on.[7] Literary tools[8] creatively conceal the explicit nature of rap artists’ confrontations, causing Black expressionism to be misinterpreted and misunderstood. Critics of rap music fail to visualize the emotion, talent, and intellect rap artists embed within their songs, due to the language barrier between Black individualism and the criminal justice system.[9] Most fail to acknowledge and peel back the layers of rap music, mirroring the failure of slave overseers to peel back the meanings of plantation slave songs.[10]

The cultural colloquialisms, AAVE (African American Vernacular English), and poetic rhythms demonstrate the need for rap and hip-hop music’s consideration as a form of literary art, and not criminal evidence. As an art form, rap music deserves the utmost protection within the criminal justice system. Criminalizing song artists for the content of their lyrics promotes prejudiced decision making in the justice system because using lyrics as evidence targets and disproportionately impacts Black artists.[11] Prosecutors attempt to use rap lyrics against defendants in two ways. First, prosecutors are conscious of a juries’ implicit bias against rap music and its artists,[12] hoping that they’ll conflate a defendant’s expression with what is depicted in the song.[13] Second, prosecutors may introduce rap videos into evidence in an attempt to show the “existence of a criminal enterprise, association with other members, familiarity with firearms, and a motive to commit certain crimes.”[14] Through justified association between rap music and violent crimes, it creates a horrible and restrictive suggestion that the genre, and its artists, glorify or condone violent and other stereotypes contemporaneously mentioned with Black art and its people.

Labeling rap lyrics as criminal also disproportionately impacts the rap music genre.[15] This label will have a chilling effect on Black speech if rap lyrics continue to be hyper-criminalized by prosecution.[16] Rap artists will focus more on evading criminal prosecution based on their lyrics, and less on artistic excellence. The hip-hop community is simultaneously under attack and under surveillance.[17] Historically, and now, individual rap artists and rap groups have been surveilled—via eavesdropping, tracking, and online monitoring.[18] Now, the unwelcome intrusion into rap and hip-hop culture has transformed into criminalizing an artist’s words and not their actions.

In the context of rap lyrics in criminal proceedings, the Black existence does not survive prosecutorial discretion. Prosecutors are able to prove elements of a crime by circumstantial evidence. Instead, the Black existence is contextual and layered—like the perfect verse over a tight beat.[19] All rap music needs is for the world to finally give it a fighting chance.[20]

[1] Sirens – Little Brother, Genius, https://genius.com/Little-brother-sirens-lyrics (last visited Mar. 18, 2022); See generally Christina Reyna, Mark Brandt, & G. Tendayi Viki, Blame It on Hip-Hop: Anti-Rap Attitudes as a Proxy for Prejudice, 12(3), Gʀᴘ. Pʀᴏᴄᴇssᴇs & Iɴᴛᴇʀɢʀᴏᴜᴘ Rᴇʟᴀᴛɪᴏɴs 361 (2009) (discussing how negative stereotypes of rap music influence attitudes of Blackness and Black people.)

[2] Reyna, et.al, supra note 1, at 362.

[3] Vidhaath Sripathi, Bars Behind Bars: Rap Lyrics, Character Evidence, and State v. Skinner, 24 J. Gᴇɴᴅᴇʀ, Rᴀᴄᴇ, & Jᴜsᴛ. 207, 208 (2021).

[4] Becky Blanchard, The Social Significance of Rap & Hip-Hop Culture, Edge (July 26, 1999), https://web.stanford.edu/class/e297c/poverty_prejudice/mediarace/socialsignificance.htm.

[5] Joseph Paul Eiswerth, Rap Music As Protest: A Rhetorical Analysis of Public Enemy’s Lyrics, UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds/583/.

[6] Id.

[7] Donald F. Tibbs & Shelly Chauncey, From Slavery to Hip-Hop: Punishing Black Speech and What’s “Unconstitutional” About Prosecuting Young Black Men Through Art, 52 Wash. Univ. j.l. & Pol’y. 33, 51 (2016).

[8] See, e.g., literary tools such as metaphors, rhyme and rhythm, similes, attention to language, imagery, and character personas. Cynthia Lee, Rap Lyrics as Literature, UCLA Newsroom: MAGAZINE, Feb. 15, 2022, https://newsroom.ucla.edu/magazine/lectures-lyrics-hip-hop-rap-poetry.

[9] Donald F. Tibbs & Shelly Chauncey, From Slavery to Hip-Hop: Punishing Black Speech and What’s “Unconstitutional” About Prosecuting Young Black Men Through Art, 52 Wash. Univ. j. l. & Pol’y. 33, 51 (2016).

[10] Id.

[11] Erin Lutes, James Purdon, Henry F. Fradella, When Music Takes The Stand: A Content Analysis of How Courts Use and Misuse Rap Lyrics in Criminal Cases, 46 Am. J. Crim. L. 77, 87 (2019).

[12] Sripathi, supra note 3, at 219.

[13] Erik Nielson, Prosecutors would rather read rap as a threat than as art, Wash. Post, Dec. 5, 2014, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/prosecutors-would-rather-read-rap-as-a-threat-than-as-art/2014/12/05/80e77fc8-7b3e-11e4-b821-503cc7efed9e_story.html.

[14] David L. Hudson, Jr., Rap Music and the First Amendment, The First Amendment Encyclopedia, Middle Tenn. State Univ. (2018).

[15] Jason E. Powell, R.A.P.: Rule Against Perps (Who Write Rhymes), 41 Rutgers L.J 479, 516 (2021).

[16] Id.

[17] Andrea L. Dennis, The Music of Mass Incarceration, ABA (Nov.–Dec. 2020), https://www.americanbar.org/groups/intellectual_property_law/publications/landslide/2020-21/november-december/music-mass-incarceration/.

[18] Id.

[19] Brown Sugar (Fox Searchlight Pictures Oct. 11, 2002).

[20] Amy Smolcic, Is Rap Music Poetry?, Bowen St Press, (Sept. 28, 2016), http://bowenstreetpress.com/blog/2016/9/28/is-rap-music-poetry.